The objective of this Standard is to establish the principles that an entity shall apply to report useful information to users of financial statements about the nature, amount, timing and uncertainty of revenue and cash flows arising from a contract with a customer.

Preamble

Pronouncement

This compiled Standard applies to annual periods beginning on or after 1 July 2022 but before 1 January 2023. Earlier application is permitted for annual periods beginning before 1 July 2022. It incorporates relevant amendments made up to and including 3 May 2022.

Prepared on 15 September 2022 by the staff of the Australian Accounting Standards Board.

Compilation no. 7

Compilation date: 30 June 2022

Obtaining copies of Accounting Standards

Compiled versions of Standards, original Standards and amending Standards (see Compilation Details) are available on the AASB website: www.aasb.gov.au.

Australian Accounting Standards Board

PO Box 204

Collins Street West

Victoria 8007

AUSTRALIA

Phone: (03) 9617 7600

E-mail: [email protected]

Website: www.aasb.gov.au

Other enquiries

Phone: (03) 9617 7600

E-mail: [email protected]

Copyright

© Commonwealth of Australia 2022

This compiled AASB Standard contains IFRS Foundation copyright material. Digital devices and links are copyright of the Commonwealth. Reproduction within Australia in unaltered form (retaining this notice) is permitted for personal and non-commercial use subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgment of the source. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights for commercial purposes within Australia should be addressed to The Managing Director, Australian Accounting Standards Board, PO Box 204, Collins Street West, Victoria 8007.

All existing rights in this material are reserved outside Australia. Reproduction outside Australia in unaltered form (retaining this notice) is permitted for personal and non-commercial use only. Further information and requests for authorisation to reproduce IFRS Foundation copyright material for commercial purposes outside Australia should be addressed to the IFRS Foundation at www.ifrs.org.

Rubric

Australian Accounting Standard AASB 15 Revenue from Contracts with Customers (as amended) is set out in paragraphs 1 – 129 and Appendices A – C and E – G. All the paragraphs have equal authority. Paragraphs in bold type state the main principles. Terms defined in Appendices A and A.1 are in italics the first time they appear in the Standard. AASB 15 is to be read in the context of other Australian Accounting Standards, including AASB 1048 Interpretation of Standards, which identifies the Australian Accounting Interpretations, and AASB 1057 Application of Australian Accounting Standards. In the absence of explicit guidance, AASB 108 Accounting Policies, Changes in Accounting Estimates and Errors provides a basis for selecting and applying accounting policies.

Comparison with IFRS 15

AASB 15 Revenue from Contracts with Customers as amended incorporates IFRS 15 Revenue from Contracts with Customers as issued and amended by the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). Australian‑specific paragraphs (which are not included in IFRS 15) are identified with the prefix “Aus”. Paragraphs that apply only to not-for-profit entities begin by identifying their limited applicability.

Tier 1

For-profit entities complying with AASB 15 also comply with IFRS 15.

Not-for-profit entities’ compliance with IFRS 15 will depend on whether any “Aus” paragraphs that specifically apply to not-for-profit entities provide additional guidance or contain applicable requirements that are inconsistent with IFRS 15.

Tier 2

Entities preparing general purpose financial statements under Australian Accounting Standards – Simplified Disclosures (Tier 2) will not be in compliance with IFRS Standards.

AASB 1053 Application of Tiers of Australian Accounting Standards explains the two tiers of reporting requirements.

Accounting Standard AASB 15

The Australian Accounting Standards Board made Accounting Standard AASB 15 Revenue from Contracts with Customers under section 334 of the Corporations Act 2001 on 12 December 2014.

This compiled version of AASB 15 applies to annual periods beginning on or after 1 July 2022 but before 1 January 2023. It incorporates relevant amendments contained in other AASB Standards made by the AASB up to and including 3 May 2022 (see Compilation Details).

Objective

Meeting the objective

2

To meet the objective in paragraph 1, the core principle of this Standard is that an entity shall recognise revenue to depict the transfer of promised goods or services to customers in an amount that reflects the consideration to which the entity expects to be entitled in exchange for those goods or services.

3

An entity shall consider the terms of the contract and all relevant facts and circumstances when applying this Standard. An entity shall apply this Standard, including the use of any practical expedients, consistently to contracts with similar characteristics and in similar circumstances.

4

This Standard specifies the accounting for an individual contract with a customer. However, as a practical expedient, an entity may apply this Standard to a portfolio of contracts (or performance obligations) with similar characteristics if the entity reasonably expects that the effects on the financial statements of applying this Standard to the portfolio would not differ materially from applying this Standard to the individual contracts (or performance obligations) within that portfolio. When accounting for a portfolio, an entity shall use estimates and assumptions that reflect the size and composition of the portfolio.

Scope

5

An entity shall apply this Standard to all contracts with customers, except the following:

(a) lease contracts within the scope of AASB 16 Leases;

(b) insurance contracts within the scope of AASB 4 Insurance Contracts;

(c) financial instruments and other contractual rights or obligations within the scope of AASB 9 Financial Instruments, AASB 10 Consolidated Financial Statements, AASB 11 Joint Arrangements, AASB 127 Separate Financial Statements and AASB 128 Investments in Associates and Joint Ventures; and

(d) non-monetary exchanges between entities in the same line of business to facilitate sales to customers or potential customers. For example, this Standard would not apply to a contract between two oil companies that agree to an exchange of oil to fulfil demand from their customers in different specified locations on a timely basis.

Aus5.1

In addition to paragraph 5, in respect of not-for-profit entities, a transfer of a financial asset to enable an entity to acquire or construct a recognisable non-financial asset that is to be controlled by the entity, as described in AASB 1058 Income of Not-for-Profit Entities, is not within the scope of this Standard.

Aus5.2

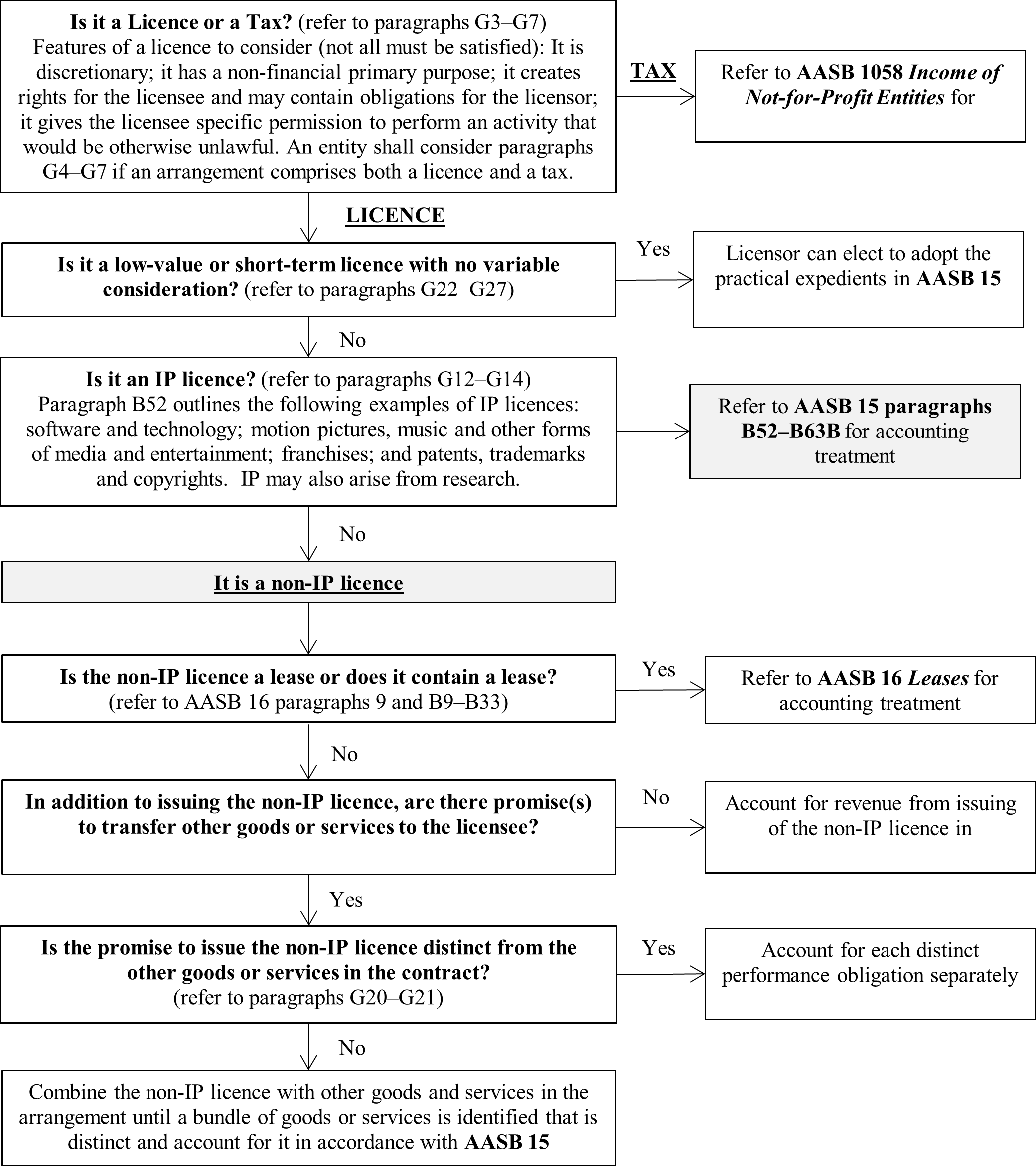

Notwithstanding paragraph 5, in respect of not-for-profit public sector licensors, this Standard also applies to licences issued, other than licences subject to AASB 16 Leases, or transactions subject to AASB 1059 Service Concession Arrangements: Grantors, irrespective of whether the licences are contracts with customers. Licences include those arising from statutory requirements. Guidance on applying this Standard to licences is set out in Appendix G, including the distinction between a licence and a tax.

6

An entity shall apply this Standard to a contract (other than a contract listed in paragraph 5) only if the counterparty to the contract is a customer. A customer is a party that has contracted with an entity to obtain goods or services that are an output of the entity’s ordinary activities in exchange for consideration. A counterparty to the contract would not be a customer if, for example, the counterparty has contracted with the entity to participate in an activity or process in which the parties to the contract share in the risks and benefits that result from the activity or process (such as developing an asset in a collaboration arrangement) rather than to obtain the output of the entity’s ordinary activities.

7

A contract with a customer may be partially within the scope of this Standard and partially within the scope of other Standards listed in paragraph 5.

(a) If the other Standards specify how to separate and/or initially measure one or more parts of the contract, then an entity shall first apply the separation and/or measurement requirements in those Standards. An entity shall exclude from the transaction price the amount of the part (or parts) of the contract that are initially measured in accordance with other Standards and shall apply paragraphs 73–86 to allocate the amount of the transaction price that remains (if any) to each performance obligation within the scope of this Standard and to any other parts of the contract identified by paragraph 7(b).

Aus7.1

For not-for-profit entities, a contract may also be partially within the scope of this Standard and partially within the scope of AASB 1058.

8

This Standard specifies the accounting for the incremental costs of obtaining a contract with a customer and for the costs incurred to fulfil a contract with a customer if those costs are not within the scope of another Standard (see paragraphs 91–104). An entity shall apply those paragraphs only to the costs incurred that relate to a contract with a customer (or part of that contract) that is within the scope of this Standard.

Recognition exemptions (paragraphs G22–G27)

Aus8.1

Except as specified in paragraph Aus8.2, a not-for-profit public sector licensor may elect not to apply the requirements in paragraphs 9–90 (and accompanying Application Guidance) to:

(a) short-term licences; and

(b) licences for which the transaction price is of low value.

Aus8.2

The option allowed in paragraph Aus8.1 is not available to licences that have variable consideration in their terms and conditions (see paragraphs 50–59 for identifying and accounting for variable consideration).

Aus8.3

If in accordance with paragraph Aus8.1 a not-for-profit public sector licensor elects not to apply the requirements in paragraphs 9–90 (and accompanying Application Guidance) to either short-term licences or licences for which the transaction price is of low value, the licensor shall recognise the revenue associated with those licences either at the point in time the licence is issued, or on a straight-line basis over the licence term or another systematic basis.

Aus8.4

If in accordance with paragraph Aus8.1 a not-for-profit public sector licensor elects not to apply the requirements in paragraphs 9–90 (and accompanying Application Guidance) to short-term licences, a licence shall be treated as if it is a new licence for the purposes of AASB 15 if there is:

(a) a modification to the scope of, or the consideration for, the licence; or

Aus8.5

The election for short-term licences under paragraph Aus8.1 shall be made by class of licence. A class of licences is a grouping of licences of a similar nature and similar rights and obligations attached to the licence. The election for licences for which the transaction price is of low value can be made on a licence-by-licence basis.

Recognition

Identifying the contract

9

An entity shall account for a contract with a customer that is within the scope of this Standard only when all of the following criteria are met:

(b) the entity can identify each party’s rights regarding the goods or services to be transferred;

(c) the entity can identify the payment terms for the goods or services to be transferred;

(e) it is probable that the entity will collect the consideration to which it will be entitled in exchange for the goods or services that will be transferred to the customer. In evaluating whether collectability of an amount of consideration is probable, an entity shall consider only the customer’s ability and intention to pay that amount of consideration when it is due. The amount of consideration to which the entity will be entitled may be less than the price stated in the contract if the consideration is variable because the entity may offer the customer a price concession (see paragraph 52).

Aus9.1

Notwithstanding paragraph 9, in respect of not-for-profit entities, if a contract that would otherwise be within the scope of AASB 15 does not meet the criteria in paragraph 9 as it is unenforceable or not sufficiently specific, it is not a contract with a customer within the scope of AASB 15 (see paragraph F5). An entity shall consider the requirements of AASB 1058 in accounting for such contracts.

10

A contract is an agreement between two or more parties that creates enforceable rights and obligations. Enforceability of the rights and obligations in a contract is a matter of law. Contracts can be written, oral or implied by an entity’s customary business practices. The practices and processes for establishing contracts with customers vary across legal jurisdictions, industries and entities. In addition, they may vary within an entity (for example, they may depend on the class of customer or the nature of the promised goods or services). An entity shall consider those practices and processes in determining whether and when an agreement with a customer creates enforceable rights and obligations.

11

Some contracts with customers may have no fixed duration and can be terminated or modified by either party at any time. Other contracts may automatically renew on a periodic basis that is specified in the contract. An entity shall apply this Standard to the duration of the contract (ie the contractual period) in which the parties to the contract have present enforceable rights and obligations.

12

For the purpose of applying this Standard, a contract does not exist if each party to the contract has the unilateral enforceable right to terminate a wholly unperformed contract without compensating the other party (or parties). A contract is wholly unperformed if both of the following criteria are met:

(a) the entity has not yet transferred any promised goods or services to the customer; and

13

If a contract with a customer meets the criteria in paragraph 9 at contract inception, an entity shall not reassess those criteria unless there is an indication of a significant change in facts and circumstances. For example, if a customer’s ability to pay the consideration deteriorates significantly, an entity would reassess whether it is probable that the entity will collect the consideration to which the entity will be entitled in exchange for the remaining goods or services that will be transferred to the customer.

14

If a contract with a customer does not meet the criteria in paragraph 9, an entity shall continue to assess the contract to determine whether the criteria in paragraph 9 are subsequently met.

15

When a contract with a customer does not meet the criteria in paragraph 9 and an entity receives consideration from the customer, the entity shall recognise the consideration received as revenue only when either of the following events has occurred:

16

An entity shall recognise the consideration received from a customer as a liability until one of the events in paragraph 15 occurs or until the criteria in paragraph 9 are subsequently met (see paragraph 14). Depending on the facts and circumstances relating to the contract, the liability recognised represents the entity’s obligation to either transfer goods or services in the future or refund the consideration received. In either case, the liability shall be measured at the amount of consideration received from the customer.

Combination of contracts

17

An entity shall combine two or more contracts entered into at or near the same time with the same customer (or related parties of the customer) and account for the contracts as a single contract if one or more of the following criteria are met:

(a) the contracts are negotiated as a package with a single commercial objective;

(b) the amount of consideration to be paid in one contract depends on the price or performance of the other contract; or

(c) the goods or services promised in the contracts (or some goods or services promised in each of the contracts) are a single performance obligation in accordance with paragraphs 22–30.

Contract modifications

18

A contract modification is a change in the scope or price (or both) of a contract that is approved by the parties to the contract. In some industries and jurisdictions, a contract modification may be described as a change order, a variation or an amendment. A contract modification exists when the parties to a contract approve a modification that either creates new or changes existing enforceable rights and obligations of the parties to the contract. A contract modification could be approved in writing, by oral agreement or implied by customary business practices. If the parties to the contract have not approved a contract modification, an entity shall continue to apply this Standard to the existing contract until the contract modification is approved.

19

A contract modification may exist even though the parties to the contract have a dispute about the scope or price (or both) of the modification or the parties have approved a change in the scope of the contract but have not yet determined the corresponding change in price. In determining whether the rights and obligations that are created or changed by a modification are enforceable, an entity shall consider all relevant facts and circumstances including the terms of the contract and other evidence. If the parties to a contract have approved a change in the scope of the contract but have not yet determined the corresponding change in price, an entity shall estimate the change to the transaction price arising from the modification in accordance with paragraphs 50–54 on estimating variable consideration and paragraphs 56–58 on constraining estimates of variable consideration.

20

An entity shall account for a contract modification as a separate contract if both of the following conditions are present:

(a) the scope of the contract increases because of the addition of promised goods or services that are distinct (in accordance with paragraphs 26–30); and

(b) the price of the contract increases by an amount of consideration that reflects the entity’s stand-alone selling prices of the additional promised goods or services and any appropriate adjustments to that price to reflect the circumstances of the particular contract. For example, an entity may adjust the stand-alone selling price of an additional good or service for a discount that the customer receives, because it is not necessary for the entity to incur the selling-related costs that it would incur when selling a similar good or service to a new customer.

21

If a contract modification is not accounted for as a separate contract in accordance with paragraph 20, an entity shall account for the promised goods or services not yet transferred at the date of the contract modification (ie the remaining promised goods or services) in whichever of the following ways is applicable:

(a) An entity shall account for the contract modification as if it were a termination of the existing contract and the creation of a new contract, if the remaining goods or services are distinct from the goods or services transferred on or before the date of the contract modification. The amount of consideration to be allocated to the remaining performance obligations (or to the remaining distinct goods or services in a single performance obligation identified in accordance with paragraph 22(b)) is the sum of:

(ii) the consideration promised as part of the contract modification.

Identifying performance obligations

22

At contract inception, an entity shall assess the goods or services promised in a contract with a customer and shall identify as a performance obligation each promise to transfer to the customer either:

(a) a good or service (or a bundle of goods or services) that is distinct; or

(b) a series of distinct goods or services that are substantially the same and that have the same pattern of transfer to the customer (see paragraph 23).

23

A series of distinct goods or services has the same pattern of transfer to the customer if both of the following criteria are met:

(a) each distinct good or service in the series that the entity promises to transfer to the customer would meet the criteria in paragraph 35 to be a performance obligation satisfied over time; and

(b) in accordance with paragraphs 39–40, the same method would be used to measure the entity’s progress towards complete satisfaction of the performance obligation to transfer each distinct good or service in the series to the customer.

Promises in contracts with customers

24

A contract with a customer generally explicitly states the goods or services that an entity promises to transfer to a customer. However, the performance obligations identified in a contract with a customer may not be limited to the goods or services that are explicitly stated in that contract. This is because a contract with a customer may also include promises that are implied by an entity’s customary business practices, published policies or specific statements if, at the time of entering into the contract, those promises create a valid expectation of the customer that the entity will transfer a good or service to the customer.

25

Performance obligations do not include activities that an entity must undertake to fulfil a contract unless those activities transfer a good or service to a customer. For example, a services provider may need to perform various administrative tasks to set up a contract. The performance of those tasks does not transfer a service to the customer as the tasks are performed. Therefore, those setup activities are not a performance obligation.

Distinct goods or services

26

Depending on the contract, promised goods or services may include, but are not limited to, the following:

(a) sale of goods produced by an entity (for example, inventory of a manufacturer)

(b) resale of goods purchased by an entity (for example, merchandise of a retailer);

(c) resale of rights to goods or services purchased by an entity (for example, a ticket resold by an entity acting as a principal, as described in paragraphs B34–B38);

(d) performing a contractually agreed-upon task (or tasks) for a customer

(e) providing a service of standing ready to provide goods or services (for example, unspecified updates to software that are provided on a when-and-if-available basis) or of making goods or services available for a customer to use as and when the customer decides;

(f) providing a service of arranging for another party to transfer goods or services to a customer (for example, acting as an agent of another party, as described in paragraphs B34–B38);

(g) granting rights to goods or services to be provided in the future that a customer can resell or provide to its customer (for example, an entity selling a product to a retailer promises to transfer an additional good or service to an individual who purchases the product from the retailer);

(h) constructing, manufacturing or developing an asset on behalf of a customer;

(i) granting licences (see paragraphs B52–B63B); and

(j) granting options to purchase additional goods or services (when those options provide a customer with a material right, as described in paragraphs B39–B43).

Aus26.1

Notwithstanding paragraph 26(i), a not-for-profit public sector licensor shall refer to Appendix G for guidance on accounting for revenue from licences issued.

27

A good or service that is promised to a customer is distinct if both of the following criteria are met:

28

A customer can benefit from a good or service in accordance with paragraph 27(a) if the good or service could be used, consumed, sold for an amount that is greater than scrap value or otherwise held in a way that generates economic benefits. For some goods or services, a customer may be able to benefit from a good or service on its own. For other goods or services, a customer may be able to benefit from the good or service only in conjunction with other readily available resources. A readily available resource is a good or service that is sold separately (by the entity or another entity) or a resource that the customer has already obtained from the entity (including goods or services that the entity will have already transferred to the customer under the contract) or from other transactions or events. Various factors may provide evidence that the customer can benefit from a good or service either on its own or in conjunction with other readily available resources. For example, the fact that the entity regularly sells a good or service separately would indicate that a customer can benefit from the good or service on its own or with other readily available resources.

29

In assessing whether an entity’s promises to transfer goods or services to the customer are separately identifiable in accordance with paragraph 27(b), the objective is to determine whether the nature of the promise, within the context of the contract, is to transfer each of those goods or services individually or, instead, to transfer a combined item or items to which the promised goods or services are inputs. Factors that indicate that two or more promises to transfer goods or services to a customer are not separately identifiable include, but are not limited to, the following:

(c) the goods or services are highly interdependent or highly interrelated. In other words, each of the goods or services is significantly affected by one or more of the other goods or services in the contract. For example, in some cases, two or more goods or services are significantly affected by each other because the entity would not be able to fulfil its promise by transferring each of the goods or services independently.

30

If a promised good or service is not distinct, an entity shall combine that good or service with other promised goods or services until it identifies a bundle of goods or services that is distinct. In some cases, that would result in the entity accounting for all the goods or services promised in a contract as a single performance obligation.

Satisfaction of performance obligations

31

An entity shall recognise revenue when (or as) the entity satisfies a performance obligation by transferring a promised good or service (ie an asset) to a customer. An asset is transferred when (or as) the customer obtains control of that asset.

32

For each performance obligation identified in accordance with paragraphs 22–30, an entity shall determine at contract inception whether it satisfies the performance obligation over time (in accordance with paragraphs 35–37) or satisfies the performance obligation at a point in time (in accordance with paragraph 38). If an entity does not satisfy a performance obligation over time, the performance obligation is satisfied at a point in time.

33

Goods and services are assets, even if only momentarily, when they are received and used (as in the case of many services). Control of an asset refers to the ability to direct the use of, and obtain substantially all of the remaining benefits from, the asset. Control includes the ability to prevent other entities from directing the use of, and obtaining the benefits from, an asset. The benefits of an asset are the potential cash flows (inflows or savings in outflows) that can be obtained directly or indirectly in many ways, such as by:

(a) using the asset to produce goods or provide services (including public services);

(b) using the asset to enhance the value of other assets;

(c) using the asset to settle liabilities or reduce expenses;

(d) selling or exchanging the asset;

(e) pledging the asset to secure a loan; and

34

When evaluating whether a customer obtains control of an asset, an entity shall consider any agreement to repurchase the asset (see paragraphs B64–B76).

Performance obligations satisfied over time

35

An entity transfers control of a good or service over time and, therefore, satisfies a performance obligation and recognises revenue over time, if one of the following criteria is met:

(a) the customer simultaneously receives and consumes the benefits provided by the entity’s performance as the entity performs (see paragraphs B3–B4);

(b) the entity’s performance creates or enhances an asset (for example, work in progress) that the customer controls as the asset is created or enhanced (see paragraph B5); or

(c) the entity’s performance does not create an asset with an alternative use to the entity (see paragraph 36) and the entity has an enforceable right to payment for performance completed to date (see paragraph 37).

36

An asset created by an entity’s performance does not have an alternative use to an entity if the entity is either restricted contractually from readily directing the asset for another use during the creation or enhancement of that asset or limited practically from readily directing the asset in its completed state for another use. The assessment of whether an asset has an alternative use to the entity is made at contract inception. After contract inception, an entity shall not update the assessment of the alternative use of an asset unless the parties to the contract approve a contract modification that substantively changes the performance obligation. Paragraphs B6–B8 provide guidance for assessing whether an asset has an alternative use to an entity.

37

An entity shall consider the terms of the contract, as well as any laws that apply to the contract, when evaluating whether it has an enforceable right to payment for performance completed to date in accordance with paragraph 35(c). The right to payment for performance completed to date does not need to be for a fixed amount. However, at all times throughout the duration of the contract, the entity must be entitled to an amount that at least compensates the entity for performance completed to date if the contract is terminated by the customer or another party for reasons other than the entity’s failure to perform as promised. Paragraphs B9–B13 provide guidance for assessing the existence and enforceability of a right to payment and whether an entity’s right to payment would entitle the entity to be paid for its performance completed to date.

Performance obligations satisfied at a point in time

38

If a performance obligation is not satisfied over time in accordance with paragraphs 35–37, an entity satisfies the performance obligation at a point in time. To determine the point in time at which a customer obtains control of a promised asset and the entity satisfies a performance obligation, the entity shall consider the requirements for control in paragraphs 31–34. In addition, an entity shall consider indicators of the transfer of control, which include, but are not limited to, the following:

(c) The entity has transferred physical possession of the asset—the customer’s physical possession of an asset may indicate that the customer has the ability to direct the use of, and obtain substantially all of the remaining benefits from, the asset or to restrict the access of other entities to those benefits. However, physical possession may not coincide with control of an asset. For example, in some repurchase agreements and in some consignment arrangements, a customer or consignee may have physical possession of an asset that the entity controls. Conversely, in some bill-and-hold arrangements, the entity may have physical possession of an asset that the customer controls. Paragraphs B64–B76, B77–B78 and B79–B82 provide guidance on accounting for repurchase agreements, consignment arrangements and bill-and-hold arrangements, respectively.

(e) The customer has accepted the asset—the customer’s acceptance of an asset may indicate that it has obtained the ability to direct the use of, and obtain substantially all of the remaining benefits from, the asset. To evaluate the effect of a contractual customer acceptance clause on when control of an asset is transferred, an entity shall consider the guidance in paragraphs B83–B86.

Measuring progress towards complete satisfaction of a performance obligation

39

For each performance obligation satisfied over time in accordance with paragraphs 35–37, an entity shall recognise revenue over time by measuring the progress towards complete satisfaction of that performance obligation. The objective when measuring progress is to depict an entity’s performance in transferring control of goods or services promised to a customer (ie the satisfaction of an entity’s performance obligation).

40

An entity shall apply a single method of measuring progress for each performance obligation satisfied over time and the entity shall apply that method consistently to similar performance obligations and in similar circumstances. At the end of each reporting period, an entity shall remeasure its progress towards complete satisfaction of a performance obligation satisfied over time.

Methods for measuring progress

41

Appropriate methods of measuring progress include output methods and input methods. Paragraphs B14–B19 provide guidance for using output methods and input methods to measure an entity’s progress towards complete satisfaction of a performance obligation. In determining the appropriate method for measuring progress, an entity shall consider the nature of the good or service that the entity promised to transfer to the customer.

41

Appropriate methods of measuring progress include output methods and input methods. Paragraphs B14–B19 provide guidance for using output methods and input methods to measure an entity’s progress towards complete satisfaction of a performance obligation. In determining the appropriate method for measuring progress, an entity shall consider the nature of the good or service that the entity promised to transfer to the customer.

42

When applying a method for measuring progress, an entity shall exclude from the measure of progress any goods or services for which the entity does not transfer control to a customer. Conversely, an entity shall include in the measure of progress any goods or services for which the entity does transfer control to a customer when satisfying that performance obligation.

43

As circumstances change over time, an entity shall update its measure of progress to reflect any changes in the outcome of the performance obligation. Such changes to an entity’s measure of progress shall be accounted for as a change in accounting estimate in accordance with AASB 108 Accounting Policies, Changes in Accounting Estimates and Errors.

Reasonable measures of progress

44

An entity shall recognise revenue for a performance obligation satisfied over time only if the entity can reasonably measure its progress towards complete satisfaction of the performance obligation. An entity would not be able to reasonably measure its progress towards complete satisfaction of a performance obligation if it lacks reliable information that would be required to apply an appropriate method of measuring progress.

44

An entity shall recognise revenue for a performance obligation satisfied over time only if the entity can reasonably measure its progress towards complete satisfaction of the performance obligation. An entity would not be able to reasonably measure its progress towards complete satisfaction of a performance obligation if it lacks reliable information that would be required to apply an appropriate method of measuring progress.

45

In some circumstances (for example, in the early stages of a contract), an entity may not be able to reasonably measure the outcome of a performance obligation, but the entity expects to recover the costs incurred in satisfying the performance obligation. In those circumstances, the entity shall recognise revenue only to the extent of the costs incurred until such time that it can reasonably measure the outcome of the performance obligation.

Measurement

46

When (or as) a performance obligation is satisfied, an entity shall recognise as revenue the amount of the transaction price (which excludes estimates of variable consideration that are constrained in accordance with paragraphs 56–58) that is allocated to that performance obligation.

Determining the transaction price

47

An entity shall consider the terms of the contract and its customary business practices to determine the transaction price. The transaction price is the amount of consideration to which an entity expects to be entitled in exchange for transferring promised goods or services to a customer, excluding amounts collected on behalf of third parties (for example, some sales taxes). The consideration promised in a contract with a customer may include fixed amounts, variable amounts, or both.

48

The nature, timing and amount of consideration promised by a customer affect the estimate of the transaction price. When determining the transaction price, an entity shall consider the effects of all of the following:

(a) variable consideration (see paragraphs 50–55 and 59);

(b) constraining estimates of variable consideration (see paragraphs 56–58);

(c) the existence of a significant financing component in the contract (see paragraphs 60–65);

(d) non-cash consideration (see paragraphs 66–69); and

(e) consideration payable to a customer (see paragraphs 70–72).

49

For the purpose of determining the transaction price, an entity shall assume that the goods or services will be transferred to the customer as promised in accordance with the existing contract and that the contract will not be cancelled, renewed or modified.

Variable consideration

50

If the consideration promised in a contract includes a variable amount, an entity shall estimate the amount of consideration to which the entity will be entitled in exchange for transferring the promised goods or services to a customer.

51

An amount of consideration can vary because of discounts, rebates, refunds, credits, price concessions, incentives, performance bonuses, penalties or other similar items. The promised consideration can also vary if an entity’s entitlement to the consideration is contingent on the occurrence or non-occurrence of a future event. For example, an amount of consideration would be variable if either a product was sold with a right of return or a fixed amount is promised as a performance bonus on achievement of a specified milestone.

52

The variability relating to the consideration promised by a customer may be explicitly stated in the contract. In addition to the terms of the contract, the promised consideration is variable if either of the following circumstances exists:

53

An entity shall estimate an amount of variable consideration by using either of the following methods, depending on which method the entity expects to better predict the amount of consideration to which it will be entitled:

54

An entity shall apply one method consistently throughout the contract when estimating the effect of an uncertainty on an amount of variable consideration to which the entity will be entitled. In addition, an entity shall consider all the information (historical, current and forecast) that is reasonably available to the entity and shall identify a reasonable number of possible consideration amounts. The information that an entity uses to estimate the amount of variable consideration would typically be similar to the information that the entity’s management uses during the bid-and-proposal process and in establishing prices for promised goods or services.

Refund liabilities

55

An entity shall recognise a refund liability if the entity receives consideration from a customer and expects to refund some or all of that consideration to the customer. A refund liability is measured at the amount of consideration received (or receivable) for which the entity does not expect to be entitled (ie amounts not included in the transaction price). The refund liability (and corresponding change in the transaction price and, therefore, the contract liability) shall be updated at the end of each reporting period for changes in circumstances. To account for a refund liability relating to a sale with a right of return, an entity shall apply the guidance in paragraphs B20–B27.

55

An entity shall recognise a refund liability if the entity receives consideration from a customer and expects to refund some or all of that consideration to the customer. A refund liability is measured at the amount of consideration received (or receivable) for which the entity does not expect to be entitled (ie amounts not included in the transaction price). The refund liability (and corresponding change in the transaction price and, therefore, the contract liability) shall be updated at the end of each reporting period for changes in circumstances. To account for a refund liability relating to a sale with a right of return, an entity shall apply the guidance in paragraphs B20–B27.

Constraining estimates of variable consideration

56

An entity shall include in the transaction price some or all of an amount of variable consideration estimated in accordance with paragraph 53 only to the extent that it is highly probable that a significant reversal in the amount of cumulative revenue recognised will not occur when the uncertainty associated with the variable consideration is subsequently resolved.

56

An entity shall include in the transaction price some or all of an amount of variable consideration estimated in accordance with paragraph 53 only to the extent that it is highly probable that a significant reversal in the amount of cumulative revenue recognised will not occur when the uncertainty associated with the variable consideration is subsequently resolved.

57

In assessing whether it is highly probable that a significant reversal in the amount of cumulative revenue recognised will not occur once the uncertainty related to the variable consideration is subsequently resolved, an entity shall consider both the likelihood and the magnitude of the revenue reversal. Factors that could increase the likelihood or the magnitude of a revenue reversal include, but are not limited to, any of the following:

(e) the contract has a large number and broad range of possible consideration amounts.

58

An entity shall apply paragraph B63 to account for consideration in the form of a sales-based or usage-based royalty that is promised in exchange for a licence of intellectual property.

Reassessment of variable consideration

59

At the end of each reporting period, an entity shall update the estimated transaction price (including updating its assessment of whether an estimate of variable consideration is constrained) to represent faithfully the circumstances present at the end of the reporting period and the changes in circumstances during the reporting period. The entity shall account for changes in the transaction price in accordance with paragraphs 87–90.

59

At the end of each reporting period, an entity shall update the estimated transaction price (including updating its assessment of whether an estimate of variable consideration is constrained) to represent faithfully the circumstances present at the end of the reporting period and the changes in circumstances during the reporting period. The entity shall account for changes in the transaction price in accordance with paragraphs 87–90.

The existence of a significant financing component in the contract

60

In determining the transaction price, an entity shall adjust the promised amount of consideration for the effects of the time value of money if the timing of payments agreed to by the parties to the contract (either explicitly or implicitly) provides the customer or the entity with a significant benefit of financing the transfer of goods or services to the customer. In those circumstances, the contract contains a significant financing component. A significant financing component may exist regardless of whether the promise of financing is explicitly stated in the contract or implied by the payment terms agreed to by the parties to the contract.

61

The objective when adjusting the promised amount of consideration for a significant financing component is for an entity to recognise revenue at an amount that reflects the price that a customer would have paid for the promised goods or services if the customer had paid cash for those goods or services when (or as) they transfer to the customer (ie the cash selling price). An entity shall consider all relevant facts and circumstances in assessing whether a contract contains a financing component and whether that financing component is significant to the contract, including both of the following:

(b) the combined effect of both of the following:

62

Notwithstanding the assessment in paragraph 61, a contract with a customer would not have a significant financing component if any of the following factors exist:

63

As a practical expedient, an entity need not adjust the promised amount of consideration for the effects of a significant financing component if the entity expects, at contract inception, that the period between when the entity transfers a promised good or service to a customer and when the customer pays for that good or service will be one year or less.

64

To meet the objective in paragraph 61 when adjusting the promised amount of consideration for a significant financing component, an entity shall use the discount rate that would be reflected in a separate financing transaction between the entity and its customer at contract inception. That rate would reflect the credit characteristics of the party receiving financing in the contract, as well as any collateral or security provided by the customer or the entity, including assets transferred in the contract. An entity may be able to determine that rate by identifying the rate that discounts the nominal amount of the promised consideration to the price that the customer would pay in cash for the goods or services when (or as) they transfer to the customer. After contract inception, an entity shall not update the discount rate for changes in interest rates or other circumstances (such as a change in the assessment of the customer’s credit risk).

65

An entity shall present the effects of financing (interest revenue or interest expense) separately from revenue from contracts with customers in the statement of comprehensive income. Interest revenue or interest expense is recognised only to the extent that a contract asset (or receivable) or a contract liability is recognised in accounting for a contract with a customer.

Non-cash consideration

66

To determine the transaction price for contracts in which a customer promises consideration in a form other than cash, an entity shall measure the non-cash consideration (or promise of non-cash consideration) at fair value.

67

If an entity cannot reasonably estimate the fair value of the non-cash consideration, the entity shall measure the consideration indirectly by reference to the stand-alone selling price of the goods or services promised to the customer (or class of customer) in exchange for the consideration.

68

The fair value of the non-cash consideration may vary because of the form of the consideration (for example, a change in the price of a share to which an entity is entitled to receive from a customer). If the fair value of the non-cash consideration promised by a customer varies for reasons other than only the form of the consideration (for example, the fair value could vary because of the entity’s performance), an entity shall apply the requirements in paragraphs 56–58.

69

If a customer contributes goods or services (for example, materials, equipment or labour) to facilitate an entity’s fulfilment of the contract, the entity shall assess whether it obtains control of those contributed goods or services. If so, the entity shall account for the contributed goods or services as non-cash consideration received from the customer.

Consideration payable to a customer

70

Consideration payable to a customer includes cash amounts that an entity pays, or expects to pay, to the customer (or to other parties that purchase the entity’s goods or services from the customer). Consideration payable to a customer also includes credit or other items (for example, a coupon or voucher) that can be applied against amounts owed to the entity (or to other parties that purchase the entity’s goods or services from the customer). An entity shall account for consideration payable to a customer as a reduction of the transaction price and, therefore, of revenue unless the payment to the customer is in exchange for a distinct good or service (as described in paragraphs 26–30) that the customer transfers to the entity. If the consideration payable to a customer includes a variable amount, an entity shall estimate the transaction price (including assessing whether the estimate of variable consideration is constrained) in accordance with paragraphs 50–58.

71

If consideration payable to a customer is a payment for a distinct good or service from the customer, then an entity shall account for the purchase of the good or service in the same way that it accounts for other purchases from suppliers. If the amount of consideration payable to the customer exceeds the fair value of the distinct good or service that the entity receives from the customer, then the entity shall account for such an excess as a reduction of the transaction price. If the entity cannot reasonably estimate the fair value of the good or service received from the customer, it shall account for all of the consideration payable to the customer as a reduction of the transaction price.

72

Accordingly, if consideration payable to a customer is accounted for as a reduction of the transaction price, an entity shall recognise the reduction of revenue when (or as) the later of either of the following events occurs:

Allocating the transaction price to performance obligations

73

The objective when allocating the transaction price is for an entity to allocate the transaction price to each performance obligation (or distinct good or service) in an amount that depicts the amount of consideration to which the entity expects to be entitled in exchange for transferring the promised goods or services to the customer.

74

To meet the allocation objective, an entity shall allocate the transaction price to each performance obligation identified in the contract on a relative stand-alone selling price basis in accordance with paragraphs 76–80, except as specified in paragraphs 81–83 (for allocating discounts) and paragraphs 84–86 (for allocating consideration that includes variable amounts).

75

Paragraphs 76–86 do not apply if a contract has only one performance obligation. However, paragraphs 84–86 may apply if an entity promises to transfer a series of distinct goods or services identified as a single performance obligation in accordance with paragraph 22(b) and the promised consideration includes variable amounts.

Allocation based on stand-alone selling prices

76

To allocate the transaction price to each performance obligation on a relative stand-alone selling price basis, an entity shall determine the stand-alone selling price at contract inception of the distinct good or service underlying each performance obligation in the contract and allocate the transaction price in proportion to those stand-alone selling prices.

77

The stand-alone selling price is the price at which an entity would sell a promised good or service separately to a customer. The best evidence of a stand-alone selling price is the observable price of a good or service when the entity sells that good or service separately in similar circumstances and to similar customers. A contractually stated price or a list price for a good or service may be (but shall not be presumed to be) the stand-alone selling price of that good or service.

78

If a stand-alone selling price is not directly observable, an entity shall estimate the stand-alone selling price at an amount that would result in the allocation of the transaction price meeting the allocation objective in paragraph 73. When estimating a stand-alone selling price, an entity shall consider all information (including market conditions, entity-specific factors and information about the customer or class of customer) that is reasonably available to the entity. In doing so, an entity shall maximise the use of observable inputs and apply estimation methods consistently in similar circumstances.

79

Suitable methods for estimating the stand-alone selling price of a good or service include, but are not limited to, the following:

(c) Residual approach—an entity may estimate the stand-alone selling price by reference to the total transaction price less the sum of the observable stand-alone selling prices of other goods or services promised in the contract. However, an entity may use a residual approach to estimate, in accordance with paragraph 78, the stand-alone selling price of a good or service only if one of the following criteria is met:

80

A combination of methods may need to be used to estimate the stand-alone selling prices of the goods or services promised in the contract if two or more of those goods or services have highly variable or uncertain stand-alone selling prices. For example, an entity may use a residual approach to estimate the aggregate stand-alone selling price for those promised goods or services with highly variable or uncertain stand-alone selling prices and then use another method to estimate the stand-alone selling prices of the individual goods or services relative to that estimated aggregate stand-alone selling price determined by the residual approach. When an entity uses a combination of methods to estimate the stand-alone selling price of each promised good or service in the contract, the entity shall evaluate whether allocating the transaction price at those estimated stand-alone selling prices would be consistent with the allocation objective in paragraph 73 and the requirements for estimating stand-alone selling prices in paragraph 78.

Allocation of a discount

81

A customer receives a discount for purchasing a bundle of goods or services if the sum of the stand-alone selling prices of those promised goods or services in the contract exceeds the promised consideration in a contract. Except when an entity has observable evidence in accordance with paragraph 82 that the entire discount relates to only one or more, but not all, performance obligations in a contract, the entity shall allocate a discount proportionately to all performance obligations in the contract. The proportionate allocation of the discount in those circumstances is a consequence of the entity allocating the transaction price to each performance obligation on the basis of the relative stand-alone selling prices of the underlying distinct goods or services.

82

An entity shall allocate a discount entirely to one or more, but not all, performance obligations in the contract if all of the following criteria are met:

(a) the entity regularly sells each distinct good or service (or each bundle of distinct goods or services) in the contract on a stand-alone basis;

(b) the entity also regularly sells on a stand-alone basis a bundle (or bundles) of some of those distinct goods or services at a discount to the stand-alone selling prices of the goods or services in each bundle; and

83

If a discount is allocated entirely to one or more performance obligations in the contract in accordance with paragraph 82, an entity shall allocate the discount before using the residual approach to estimate the stand-alone selling price of a good or service in accordance with paragraph 79(c).

Allocation of variable consideration

84

Variable consideration that is promised in a contract may be attributable to the entire contract or to a specific part of the contract, such as either of the following:

(b) one or more, but not all, distinct goods or services promised in a series of distinct goods or services that forms part of a single performance obligation in accordance with paragraph 22(b) (for example, the consideration promised for the second year of a two-year cleaning service contract will increase on the basis of movements in a specified inflation index).

85

An entity shall allocate a variable amount (and subsequent changes to that amount) entirely to a performance obligation or to a distinct good or service that forms part of a single performance obligation in accordance with paragraph 22(b) if both of the following criteria are met:

(b) allocating the variable amount of consideration entirely to the performance obligation or the distinct good or service is consistent with the allocation objective in paragraph 73 when considering all of the performance obligations and payment terms in the contract.

86

The allocation requirements in paragraphs 73–83 shall be applied to allocate the remaining amount of the transaction price that does not meet the criteria in paragraph 85.

Changes in the transaction price

87

After contract inception, the transaction price can change for various reasons, including the resolution of uncertain events or other changes in circumstances that change the amount of consideration to which an entity expects to be entitled in exchange for the promised goods or services.

88

An entity shall allocate to the performance obligations in the contract any subsequent changes in the transaction price on the same basis as at contract inception. Consequently, an entity shall not reallocate the transaction price to reflect changes in stand-alone selling prices after contract inception. Amounts allocated to a satisfied performance obligation shall be recognised as revenue, or as a reduction of revenue, in the period in which the transaction price changes.

89

An entity shall allocate a change in the transaction price entirely to one or more, but not all, performance obligations or distinct goods or services promised in a series that forms part of a single performance obligation in accordance with paragraph 22(b) only if the criteria in paragraph 85 on allocating variable consideration are met.

90

An entity shall account for a change in the transaction price that arises as a result of a contract modification in accordance with paragraphs 18–21. However, for a change in the transaction price that occurs after a contract modification, an entity shall apply paragraphs 87–89 to allocate the change in the transaction price in whichever of the following ways is applicable:

(a) An entity shall allocate the change in the transaction price to the performance obligations identified in the contract before the modification if, and to the extent that, the change in the transaction price is attributable to an amount of variable consideration promised before the modification and the modification is accounted for in accordance with paragraph 21(a).

(b) In all other cases in which the modification was not accounted for as a separate contract in accordance with paragraph 20, an entity shall allocate the change in the transaction price to the performance obligations in the modified contract (ie the performance obligations that were unsatisfied or partially unsatisfied immediately after the modification).

Contract costs

Incremental costs of obtaining a contract

91

An entity shall recognise as an asset the incremental costs of obtaining a contract with a customer if the entity expects to recover those costs.

92

The incremental costs of obtaining a contract are those costs that an entity incurs to obtain a contract with a customer that it would not have incurred if the contract had not been obtained (for example, a sales commission).

93

Costs to obtain a contract that would have been incurred regardless of whether the contract was obtained shall be recognised as an expense when incurred, unless those costs are explicitly chargeable to the customer regardless of whether the contract is obtained.

94

As a practical expedient, an entity may recognise the incremental costs of obtaining a contract as an expense when incurred if the amortisation period of the asset that the entity otherwise would have recognised is one year or less.

Costs to fulfil a contract

95

If the costs incurred in fulfilling a contract with a customer are not within the scope of another Standard (for example, AASB 102 Inventories, AASB 116 Property, Plant and Equipment or AASB 138 Intangible Assets), an entity shall recognise an asset from the costs incurred to fulfil a contract only if those costs meet all of the following criteria:

96

For costs incurred in fulfilling a contract with a customer that are within the scope of another Standard, an entity shall account for those costs in accordance with those other Standards.

97

Costs that relate directly to a contract (or a specific anticipated contract) include any of the following:

(b) direct materials (for example, supplies used in providing the promised services to a customer);

(d) costs that are explicitly chargeable to the customer under the contract; and

98

An entity shall recognise the following costs as expenses when incurred:

(a) general and administrative costs (unless those costs are explicitly chargeable to the customer under the contract, in which case an entity shall evaluate those costs in accordance with paragraph 97);

Amortisation and impairment

99

An asset recognised in accordance with paragraph 91 or 95 shall be amortised on a systematic basis that is consistent with the transfer to the customer of the goods or services to which the asset relates. The asset may relate to goods or services to be transferred under a specific anticipated contract (as described in paragraph 95(a)).

100

An entity shall update the amortisation to reflect a significant change in the entity’s expected timing of transfer to the customer of the goods or services to which the asset relates. Such a change shall be accounted for as a change in accounting estimate in accordance with AASB 108.

101

An entity shall recognise an impairment loss in profit or loss to the extent that the carrying amount of an asset recognised in accordance with paragraph 91 or 95 exceeds:

(b) the costs that relate directly to providing those goods or services and that have not been recognised as expenses (see paragraph 97).

102

For the purposes of applying paragraph 101 to determine the amount of consideration that an entity expects to receive, an entity shall use the principles for determining the transaction price (except for the requirements in paragraphs 56–58 on constraining estimates of variable consideration) and adjust that amount to reflect the effects of the customer’s credit risk.

103

Before an entity recognises an impairment loss for an asset recognised in accordance with paragraph 91 or 95, the entity shall recognise any impairment loss for assets related to the contract that are recognised in accordance with another Standard (for example, AASB 102, AASB 116 and AASB 138). After applying the impairment test in paragraph 101, an entity shall include the resulting carrying amount of the asset recognised in accordance with paragraph 91 or 95 in the carrying amount of the cash-generating unit to which it belongs for the purpose of applying AASB 136 Impairment of Assets to that cash-generating unit.

104

An entity shall recognise in profit or loss a reversal of some or all of an impairment loss previously recognised in accordance with paragraph 101 when the impairment conditions no longer exist or have improved. The increased carrying amount of the asset shall not exceed the amount that would have been determined (net of amortisation) if no impairment loss had been recognised previously.

Presentation

105

When either party to a contract has performed, an entity shall present the contract in the statement of financial position as a contract asset or a contract liability, depending on the relationship between the entity’s performance and the customer’s payment. An entity shall present any unconditional rights to consideration separately as a receivable.

106

If a customer pays consideration, or an entity has a right to an amount of consideration that is unconditional (ie a receivable), before the entity transfers a good or service to the customer, the entity shall present the contract as a contract liability when the payment is made or the payment is due (whichever is earlier). A contract liability is an entity’s obligation to transfer goods or services to a customer for which the entity has received consideration (or an amount of consideration is due) from the customer.

107

If an entity performs by transferring goods or services to a customer before the customer pays consideration or before payment is due, the entity shall present the contract as a contract asset, excluding any amounts presented as a receivable. A contract asset is an entity’s right to consideration in exchange for goods or services that the entity has transferred to a customer. An entity shall assess a contract asset for impairment in accordance with AASB 9. An impairment of a contract asset shall be measured, presented and disclosed on the same basis as a financial asset that is within the scope of AASB 9 (see also paragraph 113(b)).

108

A receivable is an entity’s right to consideration that is unconditional. A right to consideration is unconditional if only the passage of time is required before payment of that consideration is due. For example, an entity would recognise a receivable if it has a present right to payment even though that amount may be subject to refund in the future. An entity shall account for a receivable in accordance with AASB 9. Upon initial recognition of a receivable from a contract with a customer, any difference between the measurement of the receivable in accordance with AASB 9 and the corresponding amount of revenue recognised shall be presented as an expense (for example, as an impairment loss).

109

This Standard uses the terms ‘contract asset’ and ‘contract liability’ but does not prohibit an entity from using alternative descriptions in the statement of financial position for those items. If an entity uses an alternative description for a contract asset, the entity shall provide sufficient information for a user of the financial statements to distinguish between receivables and contract assets.

Disclosure

110

The objective of the disclosure requirements is for an entity to disclose sufficient information to enable users of financial statements to understand the nature, amount, timing and uncertainty of revenue and cash flows arising from contracts with customers. To achieve that objective, an entity shall disclose qualitative and quantitative information about all of the following:

(a) its contracts with customers (see paragraphs 113–122);

(b) the significant judgements, and changes in the judgements, made in applying this Standard to those contracts (see paragraphs 123–126); and

(c) any assets recognised from the costs to obtain or fulfil a contract with a customer in accordance with paragraph 91 or 95 (see paragraphs 127–128).

111

An entity shall consider the level of detail necessary to satisfy the disclosure objective and how much emphasis to place on each of the various requirements. An entity shall aggregate or disaggregate disclosures so that useful information is not obscured by either the inclusion of a large amount of insignificant detail or the aggregation of items that have substantially different characteristics.

112

An entity need not disclose information in accordance with this Standard if it has provided the information in accordance with another Standard.

Contracts with customers

113

An entity shall disclose all of the following amounts for the reporting period unless those amounts are presented separately in the statement of comprehensive income in accordance with other Standards:

(b) any impairment losses recognised (in accordance with AASB 9) on any receivables or contract assets arising from an entity’s contracts with customers, which the entity shall disclose separately from impairment losses from other contracts.

Disaggregation of revenue

114

An entity shall disaggregate revenue recognised from contracts with customers into categories that depict how the nature, amount, timing and uncertainty of revenue and cash flows are affected by economic factors. An entity shall apply the guidance in paragraphs B87–B89 when selecting the categories to use to disaggregate revenue.

115

In addition, an entity shall disclose sufficient information to enable users of financial statements to understand the relationship between the disclosure of disaggregated revenue (in accordance with paragraph 114) and revenue information that is disclosed for each reportable segment, if the entity applies AASB 8 Operating Segments.

Contract balances

116

An entity shall disclose all of the following:

117

An entity shall explain how the timing of satisfaction of its performance obligations (see paragraph 119(a)) relates to the typical timing of payment (see paragraph 119(b)) and the effect that those factors have on the contract asset and the contract liability balances. The explanation provided may use qualitative information.

118

An entity shall provide an explanation of the significant changes in the contract asset and the contract liability balances during the reporting period. The explanation shall include qualitative and quantitative information. Examples of changes in the entity’s balances of contract assets and contract liabilities include any of the following:

(a) changes due to business combinations;

(c) impairment of a contract asset;

(d) a change in the time frame for a right to consideration to become unconditional (ie for a contract asset to be reclassified to a receivable); and

Performance obligations

119

An entity shall disclose information about its performance obligations in contracts with customers, including a description of all of the following:

(b) the significant payment terms (for example, when payment is typically due, whether the contract has a significant financing component, whether the consideration amount is variable and whether the estimate of variable consideration is typically constrained in accordance with paragraphs 56–58);

(d) obligations for returns, refunds and other similar obligations; and

(e) types of warranties and related obligations.

Transaction price allocated to the remaining performance obligations

120

An entity shall disclose the following information about its remaining performance obligations:

(b) an explanation of when the entity expects to recognise as revenue the amount disclosed in accordance with paragraph 120(a), which the entity shall disclose in either of the following ways:

121

As a practical expedient, an entity need not disclose the information in paragraph 120 for a performance obligation if either of the following conditions is met:

(b) the entity recognises revenue from the satisfaction of the performance obligation in accordance with paragraph B16.

122

An entity shall explain qualitatively whether it is applying the practical expedient in paragraph 121 and whether any consideration from contracts with customers is not included in the transaction price and, therefore, not included in the information disclosed in accordance with paragraph 120. For example, an estimate of the transaction price would not include any estimated amounts of variable consideration that are constrained (see paragraphs 56–58).

Significant judgements in the application of this Standard

123

An entity shall disclose the judgements, and changes in the judgements, made in applying this Standard that significantly affect the determination of the amount and timing of revenue from contracts with customers. In particular, an entity shall explain the judgements, and changes in the judgements, used in determining both of the following:

(a) the timing of satisfaction of performance obligations (see paragraphs 124–125); and

(b) the transaction price and the amounts allocated to performance obligations (see paragraph 126).

Determining the timing of satisfaction of performance obligations

124

For performance obligations that an entity satisfies over time, an entity shall disclose both of the following:

125

For performance obligations satisfied at a point in time, an entity shall disclose the significant judgements made in evaluating when a customer obtains control of promised goods or services.

Determining the transaction price and the amounts allocated to performance obligations

126

An entity shall disclose information about the methods, inputs and assumptions used for all of the following:

(b) assessing whether an estimate of variable consideration is constrained;

(d) measuring obligations for returns, refunds and other similar obligations.

Assets recognised from the costs to obtain or fulfil a contract with a customer

127

An entity shall describe both of the following:

(a) the judgements made in determining the amount of the costs incurred to obtain or fulfil a contract with a customer (in accordance with paragraph 91 or 95); and

(b) the method it uses to determine the amortisation for each reporting period.

128

An entity shall disclose all of the following:

(a) the closing balances of assets recognised from the costs incurred to obtain or fulfil a contract with a customer (in accordance with paragraph 91 or 95), by main category of asset (for example, costs to obtain contracts with customers, pre-contract costs and setup costs); and

(b) the amount of amortisation and any impairment losses recognised in the reporting period.

Practical expedients

129

If an entity elects to use the practical expedient in either paragraph 63 (about the existence of a significant financing component) or paragraph 94 (about the incremental costs of obtaining a contract), the entity shall disclose that fact.

Appendix A -- Defined terms

This appendix is an integral part of AASB 15.

contract

A[1]

An agreement between two or more parties that creates enforceable rights and obligations.

contract asset

A[2]

An entity’s right to consideration in exchange for goods or services that the entity has transferred to a customer when that right is conditioned on something other than the passage of time (for example, the entity’s future performance).

contract liability

A[3]

An entity’s obligation to transfer goods or services to a customer for which the entity has received consideration (or the amount is due) from the customer.

customer

A[4]

A party that has contracted with an entity to obtain goods or services that are an output of the entity’s ordinary activities in exchange for consideration.

income

A[5]

Increases in economic benefits during the accounting period in the form of inflows or enhancements of assets or decreases of liabilities that result in an increase in equity, other than those relating to contributions from equity participants.

performance obligation

A[6]

A promise in a contract with a customer to transfer to the customer either:

(a) a good or service (or a bundle of goods or services) that is distinct; or

(b) a series of distinct goods or services that are substantially the same and that have the same pattern of transfer to the customer.

revenue

A[7]

Income arising in the course of an entity’s ordinary activities.

stand-alone selling price (of a good or service)

A[8]

The price at which an entity would sell a promised good or service separately to a customer.

transaction price (for a contract with a customer)

A[9]

The amount of consideration to which an entity expects to be entitled in exchange for transferring promised goods or services to a customer, excluding amounts collected on behalf of third parties.

Appendix B -- Application guidance

This appendix is an integral part of AASB 15. It describes the application of paragraphs 1–129 and has the same authority as the other parts of AASB 15.

B1

This application guidance is organised into the following categories:

(a) performance obligations satisfied over time (paragraphs B2-B13);

(b) methods for measuring progress towards complete satisfaction of a performance obligation (paragraphs B14–B19);

(c) sale with a right of return (paragraphs B20–B27);

(d) warranties (paragraphs B28–B33);

(e) principal versus agent considerations (paragraphs B34–B38);

(f) customer options for additional goods or services (paragraphs B39–B43);

(g) customers’ unexercised rights (paragraphs B44–B47);

(h) non-refundable upfront fees (and some related costs) (paragraphs B48–B51);

(i) licensing (paragraphs B52–B63B);

(j) repurchase agreements (paragraphs B64–B76);

(k) consignment arrangements (paragraphs B77–B78);

(l) bill-and-hold arrangements (paragraphs B79–B82);

(m) customer acceptance (paragraphs B83–B86); and